This month's Paper of the Month is from Public Health Nutrition and is entitled ‘Evaluating the healthiness of chain-restaurant menu items using crowdsourcing: a new method'. Lead author, Lenard I Lesser, discusses the importance of consumer education on the healthiness of fast food restaurants.

While working with adolescents, I realised that adolescents get most of their information about the healthiness of food from the food industry and the media. Before our research found that adolescents ate roughly the same amount of calories at Subway and McDonald’s, however the teens thought Subway was definitely the healthier place to eat.

What if there was an easier way to educate consumers on which restaurants were offering healthier menus? Working in Los Angeles, I noticed the letter grades the city posted on each restaurant to rate the sanitary conditions. The grades educated consumers and resulted in a 22% increase in restaurants achieving an “A” score (i.e. most sanitary), and fewer hospitalizations for food-born illness. Importantly, profits increased for restaurants with an “A” grade. Could a public health department also rate the nutritional quality of a restaurant’s menu?

The main barrier to implementing this type of system is the sheer volume of information to analyse. When nutrition researchers try to analyse foods, they often end up running nutrients through an algorithm. This leaves out a critical component of nutritional analysis: the quantity of fruits, vegetables, and nuts (FVN) in a food. We know that these are the most critical components for health, but to analyse the amounts in most restaurant foods would take months of work by a dietitian.

We sought to make this process more efficient by using: a curated database of chain restaurant foods in the United States; an established algorithm that incorporated FNV amounts; crowdsourcing to sort foods with low and high FNV amounts; and a dietitian to sort through a smaller number of complex foods.

With a 40,000 item database of foods we wanted to analyse, we realised this would not be possible without the help of computer science. If we were to rely on dietitians to fully evaluate every item, at five minutes per item, it would take one dietitian over 40 weeks of full time work, costing more than US$60,000. While there were some technology costs in setting up our system, the incremental cost for the analysis of a year of restaurant data was less than US$2,000.

We hope that our method encourages other nutrition scientists to partner with computer scientists. Computer science methods, including crowdsourcing, can vastly reduce the cost to analyse food items on chain restaurant menus. We were able to process a year’s worth of items in less than a week of working time.

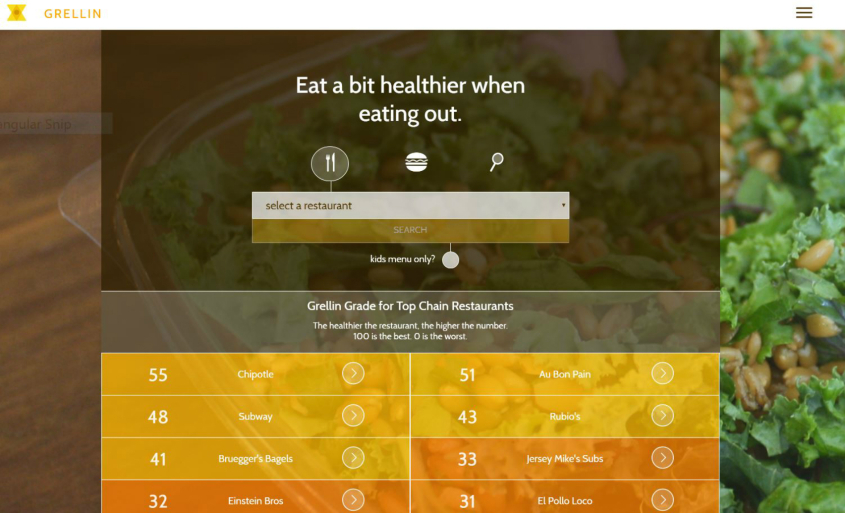

Our website, grellin.org, publishes the results of our analysis. It allows the public to compare restaurant menus on healthiness. We hope public health professionals and policy makers can use this method to efficiently analyse the impact of initiatives that aim to improve the quality of restaurant food.

Lenard I Lesser, Leslie Wu, Timothy B Matthiessen and Harold S Luft

Read the full paper here.

Image from homepage of grellin.org